Director: John Huston, Ken Hughes, Val Guest, Robert Parrish, Joe McGrath

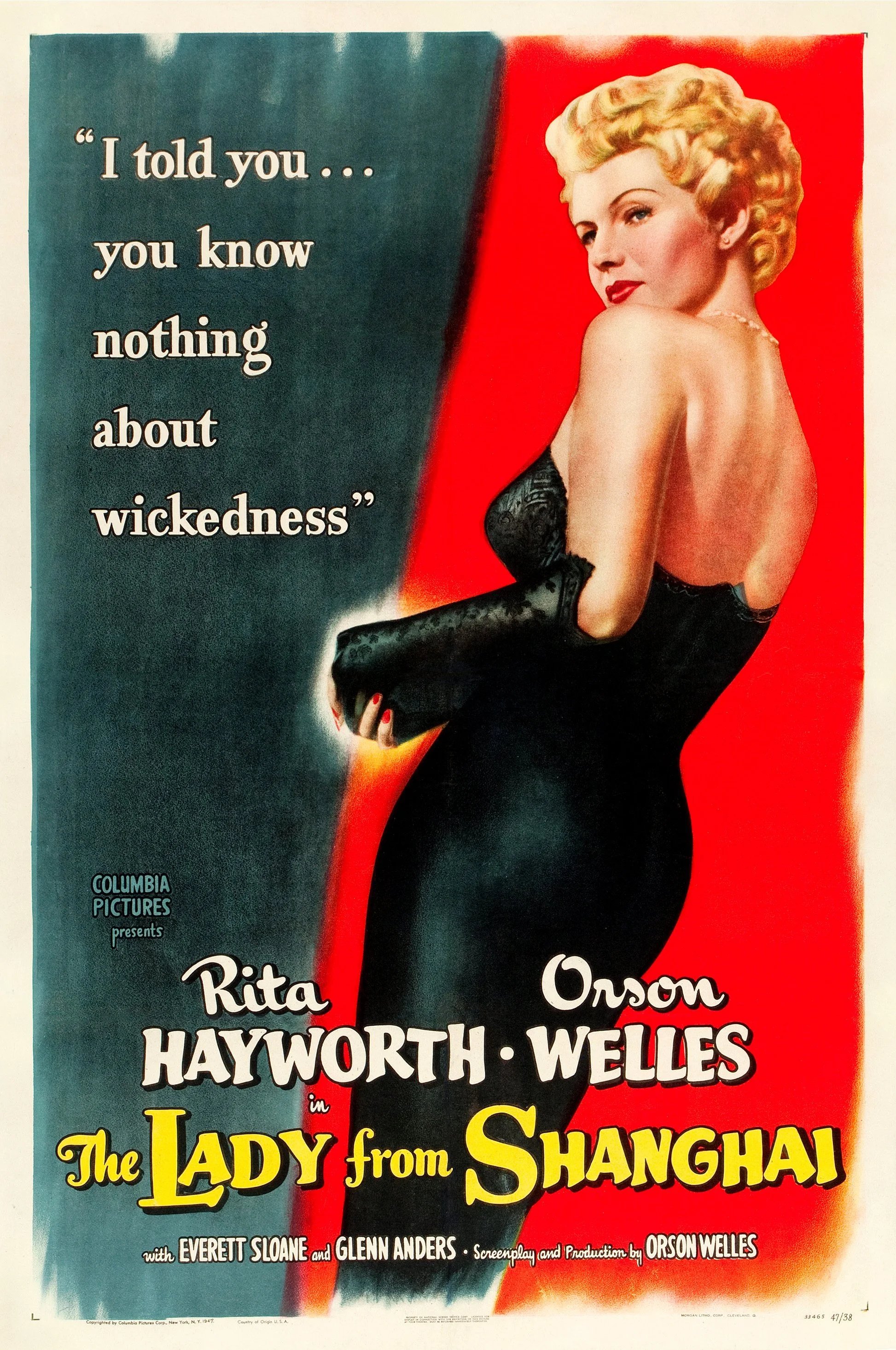

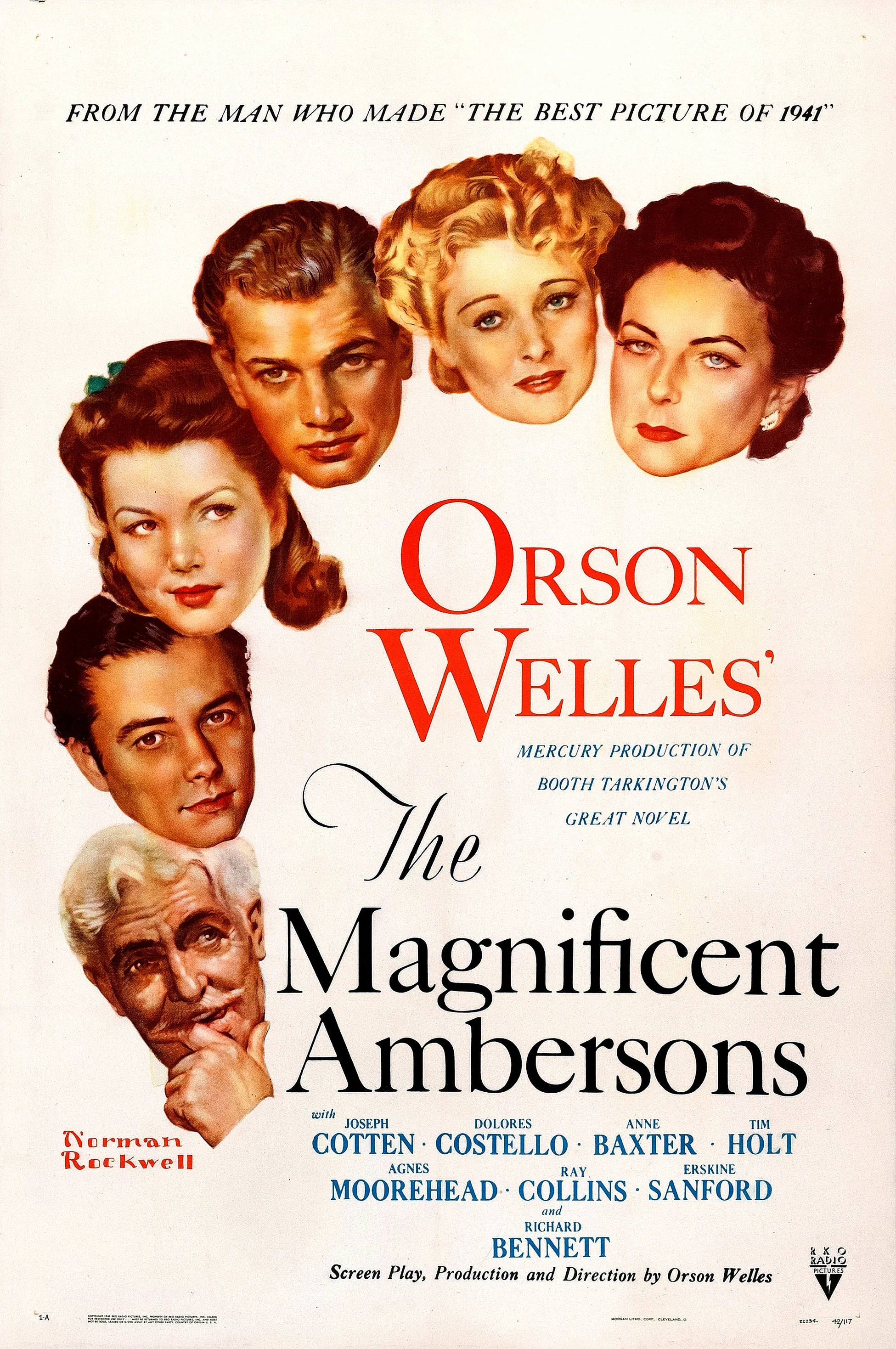

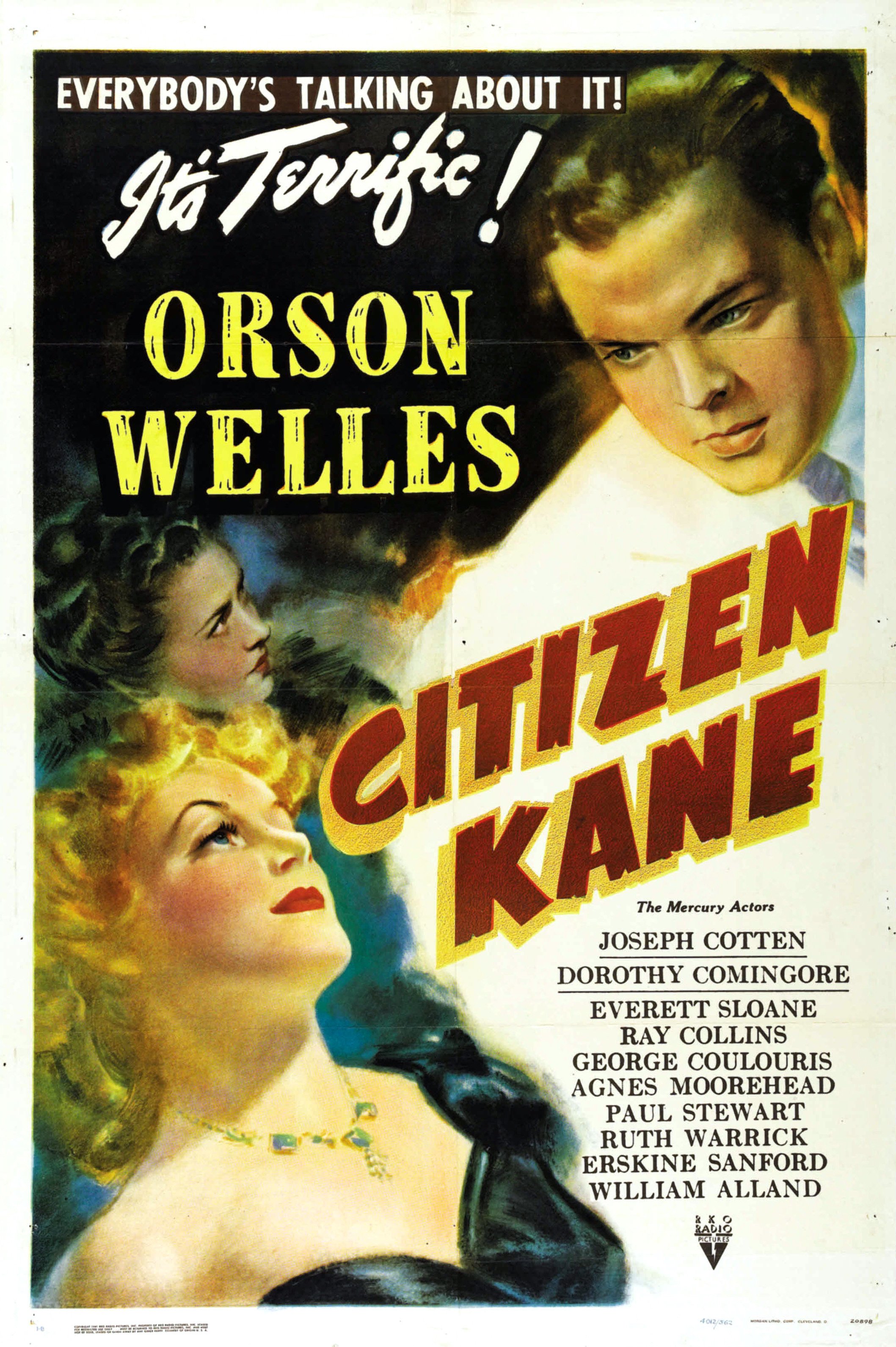

Cast: Peter Sellers, Ursula Andress, David Niven, Woody Allen, Orson Welles*

Have I Seen It Before: Yes, as one of those rogue Bond-films (I’m using each of those three words rather generously) it wasn’t one of those that I was exposed to on regular TBS Bond-a-thons, but somewhere along the way curiosity alone brought me to it. I remember my mother had a fondness for it, but I’m prepared to write that off mostly to Burt Bacharach. I thought at the time that there were a few laughs, but the whole thing dragged on far too long, which wasn’t especially damning. As a child I thought that about plenty of comedies of the era.

It's entirely possible I didn’t stick around to the end. In fact, that ending being what it is, I’m pretty sure I didn’t. Years later I came back to it. Now I know.

Did I Like It: Let’s start with the positive. A farce revolving around the idea that the world so desperately needs a James Bond that they’ll hand the name and number out to just about anybody isn’t a bad concept. Twenty years ago, if you had asked me what film desperately needed to be remade, I’d put this at the top of the list. Now that we live in a world where Casino Royale (2006) exists, one might think the case would be closed. But a conceptual remake is aching to be done, too. Just leave the Fleming canon right where it is, thank you.

What else… What else? Oh. The DVD includes a 1954 episode of the anthology series Climax!** which was the first attempt to adapt the first Fleming novel. It’s not especially good, either, but is ultimately fascinating. A completist like myself would be incomplete without both of these on his shelf.

That’d be about it. There are a fitful few laughs on display here. I’m even trying to remember them now, and they slip away the moment the film is over. Woody Allen as one of many Bond’s isn’t a bad pitch for 1967, but even that one ought to stay on the shelf in the here and now. Thin material culminates in a brief epilogue taking place in heaven, when one of the Bonds gets his final revenge on the villain of the piece. I’d say I wouldn’t identify the turn here for the sake of spoilers, but you probably wouldn’t believe me if I decided to go the other way.

This may be the most overwrought, overproduced film to be unleashed from an editing bay. I may start petitioning for the retirement of the phrase “too many cooks” and replace it with “too many directors making Royale.” It’s more words, but it feels like more descriptive. I’m paraphrasing, but Gene Siskel once described a good test of the worth of a movie is whether or not you’d rather see a documentary of the same cast having lunch. With Welles and Sellers, that’s an automatic decision from me. The movie may well have been doomed from the start.

*If I’m going to have to list five separate directors, I really ought to be allowed to list a fifth actor. Especially that one.

**Try getting that one by the censors today.